"The Silent Stage: Theater, Cinema, Writing, and Museums Amidst Political Persecution in 2000s Georgia"

- tbHUNKYDORY

- Feb 17, 2024

- 12 min read

By Tamar Barbakadze

As Georgian film director Rezo Gigineishvili says in his interview with Guardian (2023) - to experience shared by former constituent republics of the Soviet Union, from Georgia to Ukraine. “Everyone who grew up in the Soviet space was a product of a traumatizing system. It seems to me that all the post-Soviet countries are trying to get rid of the horrible legacy we inherited, which is a very painful process. And sometimes, on the way to freedom, there are wars.”

Although I never lived in the Soviet Union, I witnessed Gorbachev's "perestroika". As for the Soviet past, many of my colleagues periodically hear about it from television programs, and most often from acquaintances and friends of family members. The countdown of which begins in 1922 with the creation of the Soviet Socialist Republic and ends with its collapse in 1991, as we mistakenly thought. I even had to walk around as an October student, even though I survived the pioneer scarf; in her absence, the children were not allowed into the school building.

This entire 70-year history is remembered differently by the witnesses of history themselves, some with nostalgia for the “sweet life,” others with fear of repeating another loss of freedom.

Soviet censorship has "faded" from research from the perspective of the populations of changed countries, but it is still active, especially today. And that's where it all began.

In 1917, Vladimir Lenin signed a decree temporarily restricting freedom of speech, expression, and information until the end of the civil war. According to the order, this restriction should have been lifted immediately after the end of the civil war. However, this did not happen because Lenin believed that allowing absolute freedom of speech to “monarchists” and “anarchists” would deprive the Bolsheviks of power. In this regard, during the 70 years of the existence of the Soviet Union, censorship was in effect in each Soviet republic, the general chronology of which is systematized as follows: 1918 - According to the decree “On Control over Film Production,” private filmmakers were subordinate to local councils; 1918-1919 - the nationalization of the paper industry and the confiscation of printing houses began; 1919 - All film and photo studios were transferred to state ownership, 1921. The main censorship body "Glavlit" (Glavlit) was created - the main literary department; In 1923 - The functions of “Mtavlit” were expanded and the “Repertoire Committee” was created, which was responsible for the control of performances and events, repertoire; 1924 - Sakhkino was created, whose function was to control the content of films; 1939 - After the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, anti-fascist literature, plays, films, etc. were banned.

Thanks to the Soviet system of censorship, many authors were subject to works that were “unacceptable” to the Soviet regime and became victims of oppression, which in some cases ended in their repression or even death.

In this regard, Georgia was no exception.

After Joseph Stalin came to power in the 1930s, the Soviet system began the mass extermination of people of different views, including representatives of artists. According to the Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information, in 1937-1938, during the “Great Terror”, about 3,700 people from Georgia were convicted on the “Stalinist lists”, which were signed by Stalin himself and other members of the Politburo. The vast majority of them, more precisely 3,100 people, were sentenced to death by the Soviet authorities.

Soviet censorship and censors played an important role in these processes. Although censorship became more permissive after Stalin's death and as a result of the "two waves of de-Stalinization" than during the Stalinist period, it was not completely abolished until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Just like in Soviet cinema, censorship was no stranger to Georgian cinema either.

The history of Georgian cinema begins at the end of the 20th century. Georgian viewers became acquainted with the “Lumiere cinematograph” back in 1896. In 1900, photographer David Digmelov and his son Alexander bought a Lumiere system projector and went on tour to different parts of Georgia under the pseudonym “John Morris”.

But let's return to the topic of censorship. Simultaneously with the production of propaganda films, the regime openly opposed showing reality on the cinema screen. Some masterpieces of Georgian silent cinema were banned by Soviet censorship on charges of formalism. Some of the directors were forced to stop making films because under the regime they no longer had the opportunity to make films on their own. Sergo Faradzhanov, who was sentenced to 5 years in prison on charges of homosexuality after filming “The Color of Pomegranates,” was also punished as an example.

By the way, the West later appreciated two of Kalatozishvili’s masterpieces - “The Unsent Letter” and “I, Cuba,” filmed in Moscow. For this, America should first of all thank Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola - they revived the work of the great director almost 30 years after the premiere of these films. This seems strange - Kalatozov is still the only Soviet director (and the only Georgian director) to receive the main prize of the Cannes Film Festival - the Palme d'Or. To date, no one has repeated the record set by Kalatozov’s film “The Cranes Are Flying.” Despite this, Moscow did everything to prevent the world from seeing other masterpieces by the author of “Cranes,” which he filmed after winning the Cannes Film Festival. “I, Cuba” did not live up to the hopes of Khrushchev and Fidel. They were expecting the anthem of the Cuban revolution, but in general, they saw a poem against colonialism.

At the same time, a second problem was created for the creative people of the Soviet republics: everyone who managed to succeed was attributed to themselves as if they were of Russian heritage, and stored in their archives.

As with cinematography, the heavy hand of censorship hit theater literature and museum craft. While in Georgia the first Museum of the Caucasus was opened - the Museum of the Caucasus in 1852. At first, the East Caucasus Museum had only three rooms: ethnographic, historical, and natural science. The first with museum exhibits - 105 items (clothing, furniture, weapons, dishes, jewelry, musical instruments, money BC, memorial items, Egyptian mummies, minerals, and others). In September 1855, the first exhibition of the Caucasian Museum opened in Tbilisi.

Perhaps going back to the past may be the best way to explain the present, especially since it is not easy to remove traces of 70 years of censorship and censorship passions.

If we return to a sore subject, the Stalin era, we talk about this man, about repressions, but we don’t talk about what he left us. Somewhere in the 80s, Brezhnev said in one of his first speeches - It’s all over, the job is done, the goal is achieved, the homo-Soviet is out... And indeed, he was a Soviet man, afraid of freedom and tied to the state.

The most difficult thing today was to overcome the presence of initiative. As, for example, it affects people working in government agencies, who control what can and cannot be said through self-censorship.

The faster we forget about life in the Soviet Union, the more freedom grows in us. A new generation has come, as I mentioned above, who only heard about the Soviet Union from books, while we are the generation that had direct contact with the regime, so they require more repression for censorship in our modern era.

Today, the policy of non-provocations by Russia has turned into a policy of re-Stalinization” (Executive Director of the Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information Georgiy Kldiashvili). “It is a fact that 2023 turned out to be the most difficult year for culture,” “Even though 30 years have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgian society and the political class have still not been able to evaluate this totalitarian regime both legally and politically, but also morally,” said Sovlab founder Nino Lezhava on a popular TV show.

After the Rose Revolution, we could not think that during the existence of independent Georgia, after so many years, we would have to fight for fundamental issues, we are in the process of European integration and know how to improve the situation, laws, cultural management system and the state system management in general. How to decentralize, and how to democratically develop institutions, including the cultural sector, which is financed only by the state. We know that we need to move from one situation to another situation. When culture, theater, fine arts, and cinema are used for propaganda to turn society into a mass. And we knew and knew that we needed to move to a different context when the state must develop culture and finance it to strengthen an independent, free individual and civil society, not vice versa.

The field of culture has more or less coalesced around certain values. We have always missed the solidarity of a professional in one field with another professional, whether he showed empathy or not, whether he was angry over disrespectful exposure.

Even now, we doubt that we care about certain institutions, but are we properly concerned about rights being violated, creative censorship being declared, and whether we can unite around such meanings and ideas?

The opposite happened, it is 2023-2024, and we have a minister who believes that culture and other branches of the arts should only be funded if he gets the same again strictly and under great pressure - the faceless mass of society who can just obey and nothing more. It turns out that we, previously, in the evenings, having the opportunity to conduct secret conversations in the kitchen under the crackling of a kerosene lamp, missed something and gave up. We have a language of malice and hatred, a minister of culture, and a cultural politician who believes that she is only a minister for her constituents and promotes violent groups that oppose democracy and liberal values.

It’s nice that these issues are being discussed in the theater sphere, despite the fact that theater, like cinema, is extremely financially dependent on the state and the private sector is not so strong. The theater, for example, is completely dependent on government funding and therefore cannot earn even 75% from outside in the form of a grant, because large international organizations do not finance something that is created only for local audiences.

“The largest sector, which is subordinate to the current Minister of Culture Tea Tsulukiani, who publicly demanded that even a play be approved with him, was ridiculed by young people, and modern theater critics established the theater award “Tavisupali” (free), which is not called by this name. Each winner there spoke the sacred words that “art is political, independent and alive.” What bothered the conformists was how the audience reacted to it: with 500 young theatergoers, it was a big party." - Sofia Kilasonia (art connoisseur) - "There was almost no space left where one could speak freely."

2023 turned out to be the most difficult year for culture, there is not a single area left in this area that the Minister of Culture would not think about, from which this repressive policy would not be implemented, therefore, a unity that is consolidated, but still locked in a shell, on the one hand, film people are united in their field, writers in their field, museum workers in their museum activities. But a rally by all of them as a united force against this policy has not yet happened, and no one can name the reason why representatives of this repressed region cannot hear the main demand, the resignation of the Minister of Culture, when Iulon Gagoshidze and Donara Shanidze were fired and Russian Mitrakov was invited.

"Stalin's repressions were accompanied by very big changes in culture and an ideological whirlwind, when he made culture completely centralized and told it what to say," art critic Tamar Amashukeli - The Georgian state, neither then nor today, does anything to eliminate it, not even trying to organize artistic and government parties.

All this is a kind of leitmotif following the history of independent Georgia. If you speak out against the government, you will not receive funding, the singer will be banned from singing. And this remains so, despite the changes in the country. There is no innovation in this direction, no one wants to change the situation, and art always remains tied to power, the most powerful weapon of obedience.

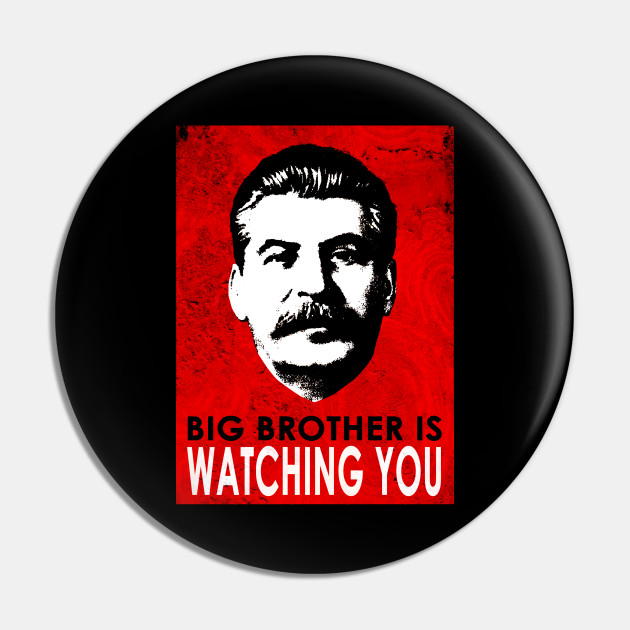

The new generation seems freer than the homo-Soviet, frightened by the invisible Big Brother-observer. Accordingly, repression by the authorities has become much harsher, and they have to be controlled with an iron fist. Yes, and today, as in the era of the red regime, art is controlled by officials, party groups, and not by specialists in this field.

Meanwhile, unprecedented generosity from the government in Berlin. An unprecedented number of delegations of 32 people will present the stand of the National Film Center of the Ministry of Culture at the 74th Berlin International Film Festival Film Market (EFM). For example, at the Berlinale film fair this year: While the Estonian Film Institute will have 9 representatives; Czech Film Fund – 5; French National Film Center - 8; National Film Center of Georgia – 32.

According to the EFM website, which contains lists of organizations and their official representatives, the film center’s delegation includes presenters from the government propaganda channel POSTV and other complete strangers, presented as film export specialists. Commenting like:

“The first Georgian stand is being created there. Accordingly, I will cover this as a cultural critic and one of the specialists in this field.”

For information, the Georgian stand will not be presented at the Berlinale for the first time and has a long history dating back more than 15 years.

In short, a whole plane, Georgians.

It is impossible to avoid another “scandal” since public art is financed from public funds. This is one of the main components of publicity and the public must be informed about it. People who look at the work need to know that this work is funded by the taxes they pay and belongs to them, their city. Knowing this gives people a sense of ownership/belonging and increases recognition and interest in the job.

In recent days, the social network has been full of conversations about the new work of Georgiy Khanashvili - “Weave of Time”. The statue was installed in Saarbrücken Square in Tbilisi on the initiative of the Tbilisi Public Art Foundation. The Foundation is an institution created by the Tbilisi City Hall to encourage creative interaction in public places and increase public awareness of contemporary art. Within the framework of this project, three works have already been placed in Tbilisi, although until now the activities of the foundation can be said to have remained unnoticed by the general public.

Controversies caused by the work of Georgiy Khanashvili. He is among a small list of artists who have made a name for themselves in contemporary Georgian art, demonstrating quality in both technical and conceptual directions.

For example, what do you know about Georgian sculpture? If you think carefully or dig around on the Internet, you will get this little chronology: chamber sculptures of the 19th-20th century, sculptures of the aesthetics of the pantheon, later sculptures of socialist realism, and their psychedelic continuation - Zurab Tsereteli.

In a country like Georgia (especially), where the general public is not familiar with contemporary art, its mission is to go beyond the white walls and make friends with everyday life.

When it comes to public art, the key word is “public.” What does public art mean? This means both the visual perception of the work and its understanding. Works created for a general audience, whether they convey a complex message or not, are often simple in form because the public space is more open to people rather than the other way around. If a work is difficult to understand or raises many questions in the viewer, this not only brings art closer to everyday life but, on the contrary, increases the distance between society and art, since the viewer distances himself from what he does not understand.

There can be many variations of such processes. It may begin immediately before the publication of the work and continue throughout its existence. From simple street surveys to television or educational programs, all methods of informing and engaging the public are acceptable.

Public art is not only created by artists and curators. This requires the participation of an architect, an art historian, an urbanist, and even a sociologist. The location chosen for public art, and its proportions should be appropriate to the environment in which it is located and take into account the population living in its vicinity.

To summarize all of the above, we can say that the creation of public art necessarily requires accompanying social processes.

Finally, I will end this study with where I should have started. The fact is that the order issuing this building permit and the order creating the “Public Art Fund” have the same signature. These are two hands of one person - with one he destroys and destroys the cultural heritage and appearance of the city, with the other he proposes to make art accessible to everyone. This fact in itself is ironic and, naturally, causes irritation among people who see the truth emerging on the surface.

Uncensored public art brings life to a city, and that's why it's so important. However, what kind of life can we talk about in a city where children die while playing in public places reserved for them? Where families are left homeless in a matter of seconds? Where greenery is concreted in every corner? Where is the land dying from endless and uncontrolled construction? Where is the oxygen in the air replaced by exhaust fumes and cement dust?

One of the shortcomings of our society is this double standard, which is an important reason for our current troubles.

When art appeared in the public places of the city of the descendants of Homosoveticus, those people started talking about this art, in whose daily life art is rarely seen.

“Fighters die, but the fight for freedom never dies” Charles Michel (about Navalny’s death, 02/16/2024)

Comments